"He has AIDS!"

- James B.

- Mar 14

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 15

This piece was published in 1995 in the “1 in 10” supplemental to the Boston Phoenix and deals with serosorting (a sexual risk reduction strategy where individuals choose sexual partners based on HIV status) that may be triggering to some today and unrecognizable to others in this Post-PrEP and Post-AIDS Pandemic era. Because this was the reality at that time, and the practice of many, I have not changed the language to reflect today’s culture. No offense is intended.

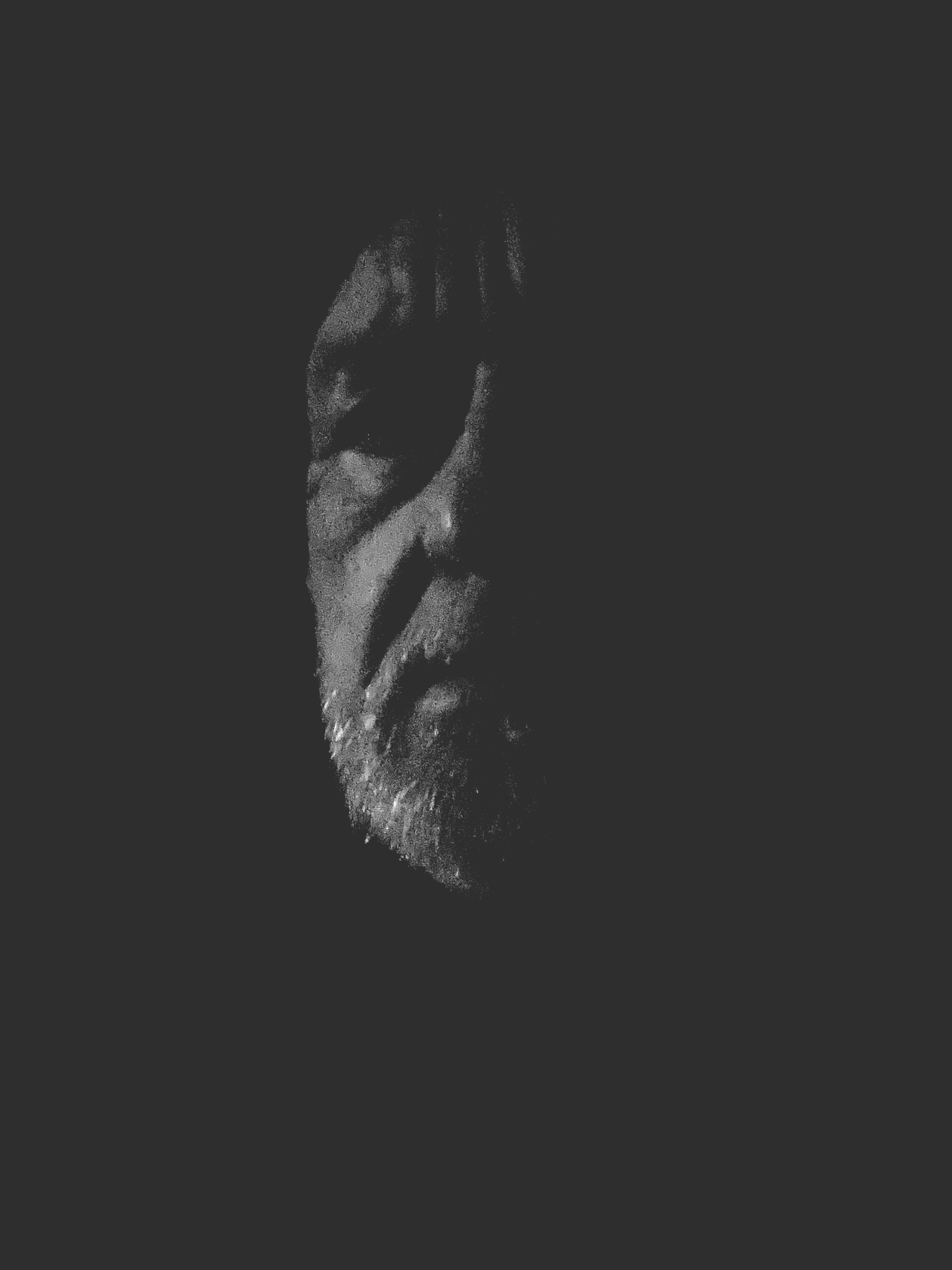

"He has AIDS,” the voice said, and the line went dead. It was two in the morning, and I was standing in my kitchen in the darkness, naked except for the sheen of sex that was seeping from me like water through a colander, leaving me dry and thirsty. I still held the phone, oblivious to the dial tone because a voice, made low and gravelly to disguise itself, spoke three words. And a stranger waited in my bed, curled under the sheets, waiting for me to replace the receiver and spoon myself next to him.

If the phone had run an hour earlier, perhaps nothing would have changed. Perhaps I would have stepped back into the bedroom and made some excuse for him to leave. But the caller called when he did, after the fact, and I found myself not as an adult in my own kitchen in Sacramento, California, receiver in hand, but as a seven-year-old on the porch of my aunt’s house in Anacoco, Louisiana, flies fighting me for the shade.

As the heat of the Louisiana summer pushed itself under the eaves, I looked out on the large yard as the rest of my family bent and hacked at the kudzu vines that swept from oak to oak, creating a canopy of green, a blanket of death.

Earlier that Sunday, my family had gathered around the dining-room table and had talked of the coming of the kudzu, how the strange vine covered everything and drew its very life from the unmoving. They had talked as if they had done this before, gathering to fight the kudzu, to push it back to the edge of the woods.

My aunt – bent, her broad back like a plank of pine – raised an ax and struck a vine. My family worked around her, each holding a machete or an ax, some a simple hoe. As a team, they would drag the vines to a pile for burning. And, as they threw a new vine on the pile, striking the ones already in place, the pile would move like snakes nailed to a floor. Behind them, there was a ridge of kudzu, a shelf of broad leaves encroaching from the deep center of the woods; it rose like the tide, covering the garden, the oaks, and half of the dying yard. With the way they had talked of its coming, I could see the kudzu vine feeding. I imagined it covering my family, their bodies becoming green bumps among the leaves. And as I had envisioned it moving toward me, snaking beneath the concrete of the porch and pushing its way through the cracks toward me, I had also heard its breathing.

***

A sound not unlike the voice that Monday morning. I replaced the receiver and walked into the bedroom, my friend already back asleep and my cat curled on his back, looking at me with eyes that begged the question. I had played safe, but it didn’t stop me from reviewing the sex act that had occupied so much of me just moments before, wondering if the enemy had slipped inside and was already at work shortening my life.

I recalled a friend’s remark over dinner months ago. “I wouldn’t sleep with someone who I knew was HIV positive,” he had said, his shoulders shrugging, hands turned up in front of him; “I’m sorry. I just wouldn’t put myself in that position.”

***

With my heart beating in my fingertips I pressed closer to this stranger with a tattoo on his arm and a last name I didn’t know. As I pushed my arm underneath him and felt the heat of him as he rolled onto his side, my heart slowed. I knew that I was safe. I also knew that a line had been drawn in the bed between us. That no matter how closely I held him that night I would never know his last name, because deep down I feared the words were true.

How many times has this happened? How many people were able to walk away because they knew too much too soon? And does he know about the voice? Does he feel it crawling between us in the bed?

I imagined the chain of voices, the trail leading from friends of his in whom he had confided, to acquaintances, to strangers who didn’t know him but knew me and had seen us together that night. Each voice climbing on top of the other until that man, dying or not, had a collective voice always following him. I traced the tattoo on his arm and remembered the times I had uttered those words, whispering to my negative friends like members in a private club. Thinking that we’re protecting one another like some virus vigilantes trying to save one another from death. I never thought that our words were filling the air, that others, hungry for life, breathed them in to find only the dead space between them.

Words screamed in warning . . .

***

… also filled the air when I was six. My friend and I on top of the hill in front of my house, Three-Wheelers tucked between our legs. Pretending to eat the baked beans that would give us gas and so turbo-charge the bikes, we looked down the hill, steep like the back of a tub.

With pretend-beans eaten, one of us would push off, the Three-Wheeler going so fast our feet couldn’t stay on the pedals that spun madly, striking our shins and ankles. But we were oblivious to the pain as the rush of the wind pulled our hair back, and we screamed our delight at the danger of it all. The other, still standing at the top, yelled, pointing out the stumps that littered the yard: “On the right!” “Watch out, turn left!” The stumps were unmovable, unchangeable, like the toes of God jutting from the ground, gnarled and cracked with clover growing in the holes.

Inevitably, we’d ram into one of them and hurl into a pile of winter leaves. Smelling like a freshly dug hole, we would crawl out from beneath and view our trophies: a sprained ankle, a gash on the forehead. But we had thought each time – before the pain and the blood – that we could steer one another to safety with our screams: “Stump at 12 O’clock!” “Look to your left!”

***

“He has AIDS!”

Feeling my agitation in his sleep, the stranger rolled over. I turned with him, keeping our bodies pressed together while my cat attacked our feet beneath the sheets, and wondered: If I hadn’t played safe, would I be angry with him? Would I consider that silence a threat?

With that man’s breath now on my neck, our feet entwined in a lazy gesture of familiarity that didn’t exist, I recalled the day I first felt that cold clenching fear of becoming infected. More than a decade ago, sitting in my parents’ living room, I saw the word AIDS emblazoned across the television. A time when California much less San Francisco, seemed like a fairy-tale place, I dramatically wrote in my journal: “To burn with the passion fire and that which quenches is certain death. Better to burn than to drown, better to wake each new day breathing fire than to drink the quenching.”

Today, I live in the land of legends, of castles in the mists. I have drunk the “quenching,” sometimes guzzling, slothful, even. But too many knights had fallen, too many friends had slipped from the edges of the dream for any of it to continue.

And yet it does, I thought while watching the clock slide toward four. We’ve just changed the rules. Personal ads with HIV statuses prominently displayed divvying up the teams for a game of Red Rover, Red Rover. We negatives in our own line, lock our hands together, and hope that our harmless conversations – “Did you hear? Jeff has ADIS.” “Oh, didn’t you know? Bret’s lover died of AIDS. “Be careful, I hear David has AIDS.” – have crossed the right names off the dance card.

I don’t know how to stop it, this collective voice we’ve begun, those who are healthy screaming in to the mouth of the canyon, the echoes of which now haunt me in the morning. It’ll take more than telling the story that woke me up like a bell calling for the end of recess.

It'll take more because I have opened my jaws and spewed my fear. My voice is out there, floating in the wind, waiting for that man with a tattoo on his arm to hear them. Of all the words available to me, I chose those three. Of all the things he needed, I gave only those three. Another type of death, not as easily seen as the kudzu cresting at the edge of the woods, but just as fatal. Just three words.

“He has AIDS.”

Comments